Born in Edmonds, Washington, author James Mace is currently a resident of Meridian, Idaho. He enlisted in the United States Air Force out of high school; three years later transferring over to the U.S. Army. After a career as a Soldier that included deploying to Iraq, in 2011 he left his full-time position with the Army National Guard to devote himself to writing.

His well-received series, "Soldier of Rome - The Artorian Chronicles," is a perennial best-seller in ancient history on Amazon. In his latest endeavors, he also branched into writing about the Napoleonic Wars. After he finishes the last of The Artorian Chronicles in 2013, he looks to expand into a series about the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879.

ONLINE LINKS:

- Website http://legionarybooks.net/

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/legionarybooks

Twitter https://twitter.com/LegionaryBooks

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.com/LegionaryBooks

Author Amazon Page http://www.amazon.com/James-Mace/e/B002BMES4O/ref=ntt_athr_dp_pel_1

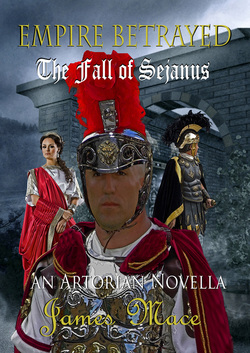

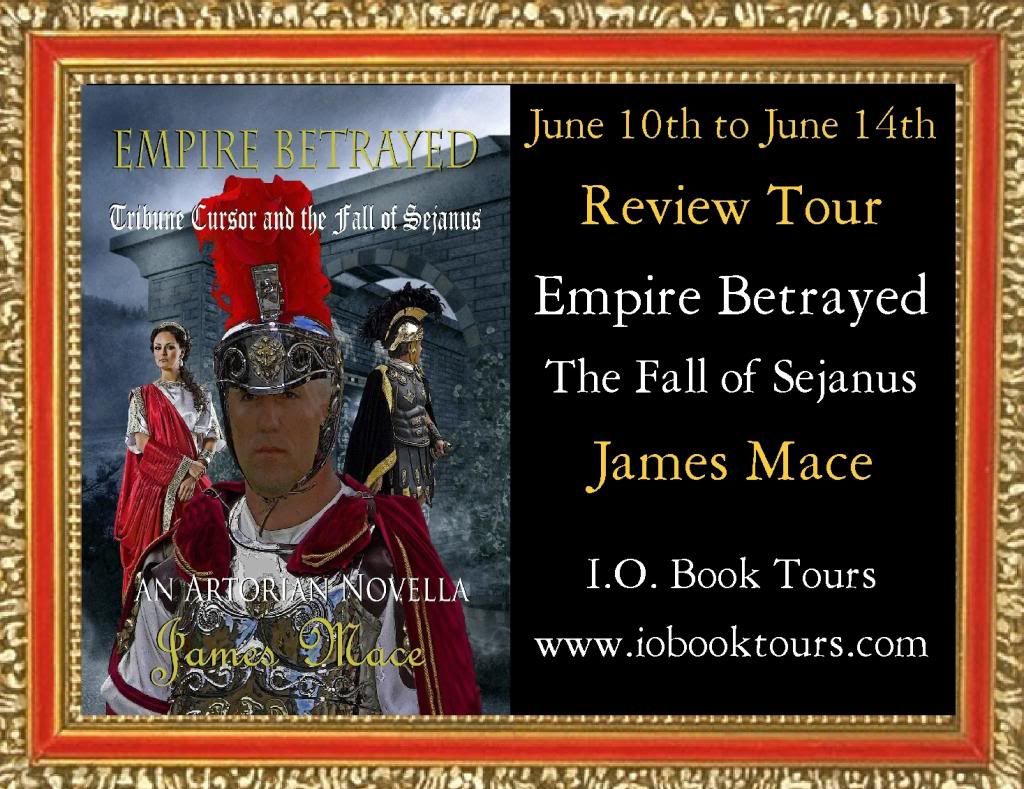

In 29 A.D., Emperor Tiberius Caesar, living in self-imposed exile on the Isle of Capri, entrusts his Praetorian Prefect, Lucius Aelius Sejanus, with the administration of the vast Roman Empire. Under Sejanus’ iron fist, and unbeknownst to Tiberius, the ranks of the Senate and equites are subsequently purged of the Praetorian’s enemies. Treason trials, once prohibited in Rome, have become commonplace as Sejanus relentlessly punishes any who would defy him in his quest for power.

After many years of commanding the cavalry of the Army of the Rhine, Tribune Aulus Nautius Cursor at last returns to Rome, amidst the turmoil. Two years later is elected as a Tribune of the Plebs; the representatives of the people who hold the power of veto over the Senate. It is Cursor who discovers Sejanus’ sinister plans; that he seeks to overthrow Tiberius and name himself Emperor.

Duty bound to save the Empire from falling further under a tyrannical usurper, Cursor resolves to unravel the conspiracy and bring the perpetrators to justice. Aiding him is an old friend; a retired Master Centurion named Gaius Calvinus. Regrettably, they know that if successful, Tiberius’ retribution will be swift and brutal, sparing neither the innocent nor the guilty. This leaves only two dark paths for Cursor and Calvinus; either allow the pending reign of terror under a ruthless usurper, or unleash the unholy vengeance of an Emperor betrayed.

Review to come once I get my copy. :)

Chapter I: All Roads to Rome

Rome

August, 29 A.D.

***

The sun had just started to break over the hills to the east as the Eternal City came into view. The well-worn road the small group travelled on was known as the Via Aurelia, or Aurelian Way. It was nearly three hundred years old and served as the main thoroughfare from Rome to the west coast of Italia. At the head of the entourage rode a man dressed in a Tribune’s armor, complete with muscled breastplate, with white leather trappings, a dark red cloak, and an ornate helmet, decorated with a lion’s head on the crown and with a magnificent red crest running front-to-back. Far from being just ceremonial, his armor had seen battle on many occasions, and even constant polishing and buffing could not eliminate the scouring from the blows of countless enemy weapons.

His name was Aulus Nautius Cursor. Taller than most men, he had a pronounced nose that was common among many of the nobility, though it was devoid of the aquiline hook. His frame was lean and more designed for speed and agility, rather than brute power. Having gone completely bald at a young age, the padded skull cap beneath his helmet was doubly important. Now in his late thirties, he’d spent nearly twenty years as a military Tribune with the Army of the Rhine; substantially longer than many of his peers. All members of the lesser-nobles of the Roman Empire, known as the Equites, were required to perform a minimum of six months with the legions. Though many stayed on longer than the compulsory time required, especially if other political or magisterial postings proved scarce, few ever made the army their primary career path. Being neither legionaries from the ranks, nor with ever having any opportunity to command legions as legates, Tribunes were confined to mostly staff duties. If one were lucky, he’d get command of a cohort of auxiliaries; the non-citizens who augmented the Roman Army with the promise of being awarded citizenship after twenty-five years of service.

For Cursor, his path had been much different. Though his name literally meant ‘runner’, and he was indeed quite nimble and fast on his feet, his true skill lay in horsemanship. His riding skills, plus natural ability for coordinating large bodies of fighting men, led to his assignment as a cavalry officer, under the tutelage of the now-legendary Commander Julius Indus. He’d also done his mandatory time as a staff officer, and was fortunate enough to have served directly under the late great, Germanicus Caesar. During the wars against the Germanic Alliance, following the disastrous ambush in Teutoburger Wald, Germanicus had demanded that all of his officers would first and foremost lead their men by their own example. In one of the few times he ever fought on foot, Cursor had accompanied his commanding general during the assault on a barbarian stronghold at Angrivarii; a terrible battle which thankfully brought the wars to an end.

Despite the accolades given to him for his bravery at Angrivarii, it was with the cavalry that the Tribune excelled, and it was following a rebellion in Gaul that he was given command of all mounted forces within the Rhine army. This was expanded even further during the Frisian Rebellion, when Cursor was handed operational control over all auxiliary forces during the campaign. With a force of ten thousand men, he had more soldiers under his charge than even the senatorial Legates who commanded the legions. It was at the Battle of Braduhenna that Cursor achieved his greatest glory, though he personally viewed it as his utmost tragedy.

“We’ve been away for far too long,” his wife, Adela Theodora, said as the city came into view over the horizon. The River Tiber stretched before them, running north to south. Just beyond was the Campus Martius, also known as the Field of Mars. A plethora of foreign temples and cults were housed here, as it also served as a place to greet dignitaries who could not for cultural reasons pass into the city proper. The most dominating feature of this district was the massive Baths of Agrippa. Beyond the field was the Capitoline; one of the famous Seven Hills that dominated Rome. The magnificent Temple of Jupiter rose from atop this hill and accented the skyline.

“To be honest, my love,” Cursor replied, “It was on the Rhine, leading my regiments, that I felt most alive.”

“And if you were still there, we should remain unmarried,” his wife replied.

“Ours was indeed an unusual courtship,” Cursor chuckled. Though arranged in the traditional sense by contract between Cursor and Adela’s father, Theodorus, Adela herself had adamantly refused to follow through with the marriage as long as Cursor was still leading men into battle.

“Father relented once he saw that I would not budge, and that you were willing to wait for me.” She had three sisters, two of whom had been widowed within their first couple years of marriage, when their husbands were killed in battle. The eldest had been wed to the Chief Tribune of the Twentieth Legion; in what their father felt was a great step forward, joining their family to the Senatorial class. Sadly, the young man was killed at Braduhenna, just four months into the marriage. He had never known that his wife was with child, though her grief would be compounded when their son was stillborn.

During what became a lengthy betrothal, Adela and her husband-to-be grew surprisingly close to each other. She had lived with family friends who owned an estate outside of Cologne, on the Rhine frontier. She therefore was able to remain close to Cursor, and was exceedingly proud of his valiant service to the Empire. However, she would not allow herself to become widowed like her sisters.

“Your father once told me that you were too intimidating for him to try and marry off to anyone else,” Cursor remembered with a laugh. “He told me I’d better not die in battle; otherwise he wouldn’t know what to do with you!” Adela simply smiled and shrugged. Being very statuesque, she was tall enough to easily look her husband in the eye, something that most normal-sized men found rather unnerving. Because Cursor treated her as an equal, their presence together made them a very strong couple.

As they reached the edge of the city, the streets were crowded with pedestrians, and they were compelled to dismount and lead their horses through the hectic thoroughfare, their travelling companions going their own ways. They skirted through a residential district, just north of the busy heart of the city. To the south was the Forum of Augustus; a small complex that housed the Temple of Mars Ultor. Further south, the great Capitoline Hill stood against the sky, with the Temple of Jupiter casting its shadow over the Roman Forum. As the road they were traveling along was crammed with street performers and observers, Cursor and Adela decided to chance going down a side street that would take them by Capitoline Hill and the Forum. Just before the Temple of Jupiter was the smaller Temple of Concord that overlooked the Forum itself.

“The Gemonian Stairs,” Cursor observed, nodding towards the long steps that led up to the temple.

“The Stairs of Mourning,” Adela added somberly. “Many a life has ended on those bloody steps.”

One would never guess from the flocks of people climbing the steps that it served as the primary place of execution for notorious criminals. Almost inconspicuously off to the right of the Temple of Concord stood the Tullianum, a prison that was used to temporarily house those awaiting trial or execution. Interestingly enough, long-term prison sentences were rare in Roman society. Punishments such as public scourging or financial penalties sufficed for minor offenses, with banishment, enslavement, or death awaiting those found guilty of capital crimes. If one looked closely, they could almost see the blackened stains on the lower steps, where the bodies of the condemned were torn to pieces by the mob. As public executions were the norm in most parts of the world, both within and outside of the Empire, and that those who met their ignominious ends on the Gemonian Stairs hardly warranted pity, Cursor and Adela paid it no more mind and continued on their way.

On the outskirts of the Forum, Cursor saw the first face he had recognized all day. The man was in his early fifties, with close-cropped hair that was a mix of black and gray. He wore a formal toga, accented with the narrow purple stripe that identified him as a member of the Equites, though he carried himself with a force of authority, like an old soldier.

“By the gods,” Cursor said with a grin, then hailing the man, “Calvinus!”

The man was startled for a moment at the call of his name, but broke into a broad grin as he walked over to Cursor and Adela. He instinctively almost saluted, but after a moment’s pause extended his hand instead.

“Tribune, sir,” he said.

“Please,” Cursor replied, clasping the old soldier’s hand, “I see by the purple stripe on your toga that you are now my peer. There is no need to call me ‘sir’.”

“Old habits,” Calvinus replied with a nonchalant shrug. He then gave a respectful nod towards the Tribune’s wife. “Lady Adela.”

“A pleasure,” she replied. “I don’t believe we’ve met.”

“Gaius Calvinus, ma’am; I served with the Twentieth Legion when your husband commanded the cavalry of the Rhine Army.”

“And as a retired Master Centurion, he was elevated into the Equites,” Cursor added.

“Rome does afford at least some opportunities to better one’s social standing,” Calvinus observed, “If one has the ambition to use them.”

“I did not know you returned to Rome,” Cursor said.

“My daughter and her family live in Neapolis,” Calvinus explained, walking with them and helping guide their way through the Forum. “This brought me close enough that I can at least pay them the occasional visit. It was bad enough that Calvina grew up hardly knowing her father, and with my grandson fast approaching manhood, I felt compelled to make up for lost time. And besides, how many retired soldiers have the opportunity to influence the governing of our beloved Empire after they remove their armor for the last time?”

“Very few,” Cursor conceded. For every hundred men who served out their term in the legions, perhaps three or four would be in a position to have a second career in continuing service to Rome. And only approximately three in every thousand ever achieved sufficient rank to elevate themselves up the social ladder.

“I felt a responsibility that once I was officially named an Equite, I needed to act as a voice for our brethren still in the ranks. I have no desire to try for a governorship or anything of that nature. However, it would be unethical if I took the privileges of being raised up within the social orders and not any of the responsibilities. If I can still be of service to Rome, I will.”

Roman society was extremely rigid in its class structure, with every citizen and non-citizen expected to know their place without question. Those within the Senatorial class were the noble patricians who lorded over the Empire, answerable only to the Emperor. All were from the oldest and wealthiest families within Rome, and while at any time as many as three hundred were sitting members of the Senate, their total number was perhaps six hundred to a thousand total households.

The Equites were the lesser nobles who provided the Empire with many of its magistrates, public officials, minor provincial governors, as well as military Tribunes and the coveted Tribunes of the Plebs. Those not born into this class could be elevated into it by serving in the army; though this often required one attaining the rank of Centurion Primus Pilus, also known as a Master Centurion. Centurions who had served as cohort commanders were also sometimes eligible. As soldiers who retired at these exalted ranks were so few in number, they made up a very small fraction of this class. All told, there were perhaps a few thousand members of the Equites, and between them and the Senate they made up the noble classes of an Empire that numbered around seventy million persons.

“Where will you be staying?” Calvinus asked as they skirted the Forum and passed the Temple of the Divine Romulus, at the start of the street known as the Via Sacra, or Sacred Way.

“I arranged purchase of a house not too far from here,” Cursor said, “Thankfully it keeps us away from the daily insanity of the Forum. We’re about a mile south of the Castra Praetoria.” The place he referred to was the central barracks of the Emperor’s Praetorian Guard.

“Ah, I’m not far from you at all,” Calvinus observed. “Well I have to be off again; remember, I have not been away from the legions for long and am still learning the ways of an Equite former soldier who still wishes to serve the public. Give yourself a day or two to get settled, and then please call upon us. Lady Adela, my wife, Petronia, would love to make your acquaintance.”

“Likewise,” Adela replied. As they watched the old soldier make this way through the crowds, she turned to her husband. “Did you know him well?”

“Well enough,” Cursor replied. “He was one of the few survivors of that disastrous ambush in Teutoburger Wald, twenty years ago. He and a young Tribune named Cassius Chaerea saved the lives of over a hundred legionaries when they cut their way out of that nightmare. It was also his legion that my men trekked forty miles in a day to relieve after they were cut off and surrounded at Braduhenna.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed