I started my adult life as a journalist, but gave it up when I realized I wasn't going to become Walter Cronkite. I grew up in small towns in Missouri and Iowa, which make my adopted hometown of Louisville look like Manhattan.

I envy the dialogue of Daniel Woodrell, the sense of place of Silas House, and how Wendell Berry makes writing seem deceptively easy. I appreciate Elmore Leonard for being Elmore Leonard. I don't write like anyone but me.

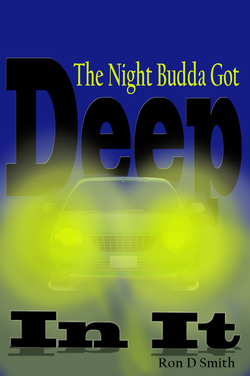

Fifteen-year-old Budda (Butter with a souther drawl) Jessico leads an unremarkable and anonymous life in suburban St. Louis. He’s not unpopular, because someone would first have to notice him. Except for the tormenting by his older brother, however, Budda is content. He follows his father’s rules and stays out of trouble. Then, at the urging of Blood Mama (his birth mother), a voice only Budda hears, he catches a bus to Kentucky to rescue his former foster sister, Addie.

As soon as Budda reaches Louisville, he goes to a McDonald’s for the first time in his life where he meets the resolute Baresha, a fellow runaway on her own adventure. Then Budda’s mission to find his sister goes downhill. He hitches a ride to Valkyrie, Addie’s hometown, in hopes of saving her from some danger Blood Mama won’t reveal. Instead, Budda encounters her blood kin, led by the ominous Odyn Starkwether and his violent brother Dickie.

A drug shipment controlled by the Starkwethers has disappeared and so has Addie. The brothers have a mess to clean up, and Budda is soon in the middle of it. At first, Budda goes along willingly, if it will help him find Addie. Before long, though, Budda realizes it’s sometimes better to stay put.

| | |

When I spent way too much time sitting on the bench my first year of Little League. I knew I should find something more productive to do with my time.

How long does it take you to write a book?

It took me more than ten years to write a biography called The Storm before the Calm: the Early Lives of Venus and Hiro. When I finished it, I still didn’t like the first few paragraphs. The first twenty attempts at the intro made me want to set my computer on fire. Instead, I set the manuscript aside for several years. The Night Budda Got Deep in It went a lot better. It took me about a year to complete, and the computer survived.

What is your work schedule like when you're writing?

I like to write in the morning when my mind is yet to be clogged with meaningless worries and other rabble. Once in awhile, I’ll write something later in the day, or even at night, but only if some great thought or character idea pops into my head.

What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

I write while I’m in the shower. The cost of replacing waterlogged laptops is starting to get a little expensive, however.

How do books get published?

Once the manuscript is finished, I hire a book cover designer and a proofreader. After that, I go through Create Space to publish the printed version. I upload a digital version to Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing. I also upload a version to Smashwords to distribute to other online outlets. I think there’s some pixie dust involved, as well.

Where do you get your information or ideas for your books?

I get information from the Internet, because we all know everything on the Internet is true. My ideas come from I wonder questions, as in “I wonder who put up that big cross next to the porn store and why…” That led to a book.

When did you write your first book and how old were you?

I was in my early thirties, about twenty years ago. I had a gotten a new Mac and wanted to prove to myself that I could write a book. I never did anything with it, because that wasn’t my intention. Two armed guards keep 24-hour watch over the manuscript should anyone get the idea to look at it.

What do you like to do when you're not writing?

I frolic in a field of daisies with my pet marmot Mathilda. Her legs are so short, however, that she’s getting a little grumpy about it.

What does your family think of your writing?

I’m afraid to ask. Actually, my wife is very supportive and is always the first to read my work. My teenage daughters are a bit more ambivalent. My older daughter read one of my books. She didn’t throw it at me when she was finished, so I’ll take that as a positive.

What was one of the most surprising things you learned in creating your books?

If you’re an indie writer, the writing is only the beginning. Even if you go the traditional publishing route, however, you still have to do a lot of work that you might expect the publisher to help with.

How many books have you written? Which is your favorite?

I’m working on my fourth book, which is my favorite because it’s the latest. But don’t tell the other books, because they’re quite sensitive. I caught The Night Budda Got Deep in It crying the other night.

Do you have any suggestions to help me become a better writer? If so, what are they?

First, and perhaps easiest, read a lot. Learn from writers you enjoy. This doesn’t mean you should copy their style, but you should note what makes them interesting to you. The story? Dialogue? Setting descriptions? And write a lot. Some writers avoid reading other books while they’re working, because they’re afraid of copying the voices of other authors. The more you write, however, this should be become less of a concern. You won’t write like anyone else.

Do you hear from your readers much? What kinds of things do they say?

They ask, “Why don’t you write something with vampires, you idiot?”

Do you like to create books for adults?

I like to write books for adult children.

What do you think makes a good story?

I like good, though damaged, characters surrounded by a lot of bad. A whole lot of bad. I’m a big fan of Daniel Woodrell, Donald Ray Pollock and William Gay. I don’t write like them, though.

As a child, what did you want to do when you grew up?

Tall. I’m six-one, but a bit of a runt in my family. I’m still hoping for a growth spurt.

10/3 Books, Books, and More Books

10/5 On Emilys Bookshelf

10/5 Comfort Books

It's an interesting viewpoint on coming of age. The characters were thought out and came across as believable. Although the protagonist is 15 years old, I would not say this is a YA read. The book has a lot of concepts and language that wouldn't be easily understood by the younger end of YA readers. I think this book would be a good read for those that like gritty books.

Although it wasn't my cup of tea, it could easily be the kind of book that the reader needs to relate a little better to characters or elements of the plot. The book isn't extremely long, so I'm going to end this review saying, "check it out if you like this sorta thing."

The Night Budda Got Deep in It

1

Budda finished the plastic-sheathed copy of Oliver Twist and jammed it into his overstuffed backpack. The book wouldn’t be due back at the school library for another week, but he already considered it stolen, because he would never return to Kirkwood High. He had never pilfered anything before. Never so much as broken curfew. And now he was running off to Kentucky. With a stolen book. With money he thieved from his brother. My, what a rebel he had become.

The library book had more or less engaged him until the end, though Budda could have made do with half as many words — a good portion of which could have been Swahili, for all he knew. He’d only decided to read the book to look and feel smarter, though that objective hadn’t been met.

Budda fantasized about a Dickens spin on his own story, one where a mysterious benefactor or long-lost relative would rescue him from his crummy life. Or, at least, what passed for crummy in the mind of a kid who felt oppressed by his loathsome big brother and fretful father. He met the basic requirements. He never met his birth parents, and he was running away from the one who raised him. Budda could envision destiny leading him to reunite with the parents he never knew, or possibly a rich, doting relative who would support him for life.

Never mind that Budda had never been to Kentucky and knew no one there except for Addie. And never mind that his family life wasn’t as bad as he imagined. Try to convince a 15-year-old differently when he has his mind made up, and see how far you get.

No Oliver Twist ending for Budda. His birth mother, who gave him up when he was a day old, overdosed in the Sikeston Motel 6. Her body was in full hypostasis when the manager discovered her the next day, a crust of vomit on the carpet where her face lay.

If she were still alive, she couldn’t have sworn on a Gideon who Budda’s biological father was. At best, she could narrow the list to three lamentable candidates — give her that much credit — but none of them had rich relatives or were prone to doting on anything other than a bottle of Old Grand Dad. Budda’s parentage was Missouri dead-end hill trash to the core. His adoptive family, even the oafish brother he hoped would someday lose a limb in a wood chipper, was quite a few steps above that.

Budda’s birth mother, the one he called Blood Mama, had kept him company ever since his foster care days. She rode with him now on the Greyhound. She was no ghost to Budda, because she was still alive as far as he knew. (The story of the Motel 6 would have to wait a while.) She was more like an invisible advisor, a constant presence who counseled him, though often wrongly, on every aspect of his life. He knew nothing about the real Blood Mama, other than that her tweaking habit had kept her from keeping him. He pictured her alive somewhere down in the Boot-heel, working on getting her life straight. Budda would give her plenty of time to make the right ways stick, and then he’d go find her, too, just like he was doing with Addie.

It was Blood Mama who convinced him to give up on his family and to take after Addie. Blood Mama said his foster sister needed saving from something, though she had been short on specifics. Budda had a feeling Blood Mama wasn’t sure herself what the trouble was. It didn’t matter. Budda had pined for his sister since she had moved out. Once he found her and rescued her from whatever mess she was in, he would start a new life in Kentucky. It couldn’t be any worse than life in Kirkwood.

Blood Mama currently advised Budda on what he should do about his father.

Don’t you think I should call him? Budda asked.

You’ll just get him riled up more. If you’re running away, you need to make a clean break of it, Blood Mama said.

I don’t want him to be worried. You know how he is. He’ll think somebody abducted me.

So you think he’ll quit worrying if he knows you run off from home and crossed three state lines to find the girl instead? Just let him be.

I won’t call him, but I should at least text him, Budda said, thumbing the keys on his phone. I won’t say where I’m going, but I’ll tell him not to worry.

Well then, he’ll be sure to sleep sound tonight, won’t he?

Budda usually listened patiently to what Blood Mama had to say, which took up a good deal of time, because the woman had an opinion on everything. With all that listening, Budda didn’t have much time for talking. The less he spoke, the dumber people thought he was. Budda didn’t fight that perception, because he believed there was a good amount of truth to it. He didn’t remember anything about his first foster family, but he theorized he had been dropped on his head, because even simple ideas came alive in his brain only with great effort, as slow to ignite as rain-sated firewood.

Budda didn’t talk out loud to Blood Mama, but he sometimes moved his lips and even gesticulated when he got lost in conversation with her. For that, kids at school thought he wasn’t only slow, but a bit off upstairs. Future wacko hobo material. That didn’t make him unique at Kirkwood High, but it didn’t guarantee a lot of prom dates either.

By the time the Greyhound reached Effingham, Illinois, commercial bus travel had lost its appeal for Budda. His bony butt was not contoured for long trips, and this was the longest one he had been on. Even worse, the driver maintained an uncomfortably cold cabin. Budda shivered for much of the trip, because he hadn’t brought anything warm to wear — it had been unseasonably mild for mid-October when he left St. Louis. Proper preparation was not his strong suit.

According to Budda’s phone, which was a scratch-and-dent, double hand-me-down Nokia from his dad to his brother to him, it was a little after eight in the evening. The aquamarine display flashed another text message from his father, which Budda deleted without reading. He turned off the audio alerts so he wouldn’t be tempted to answer when his father called or texted again, which he would do repeatedly, because the man was most in his element when he had something big to worry about. And this was a whopper.

It soon wouldn’t matter how often his dad tried to reach Budda. The Nokia’s battery was on its last bar, and he had neglected to pack its charger.

In a span of a few hours, Budda would visit three states that were new to him. He had never been to Illinois until that night, even though he lived only twenty minutes the other side of the Mississippi. He’d always imagined Illinois was just like East St. Louis from border to border. He had heard enough stories about the city across the river that he pictured it as an endless string of beer and shot bars, low wattage strip joints, and condemned two-stories that had transformed into crack houses. He also believed psycho killers prowled for innocent teenagers in every dark alley. Budda came by these ideas through his father, who had warned Budda and Lando about the atrocities that awaited them in the Land of Lincoln.

“Don’t ever, ever cross that bridge,” Dad said. “It’s easy to get lost over there. If you do, I’m afraid I’ll never see you alive again. Your name and picture will be on the front page of the Post-Dispatch when they find chunks of you in some industrial waste dump.”

What a sunny outlook the man had, yet Budda had never doubted him. Until this night, Budda had been the obedient son, the one who was never tempted to sneak across the river to that devil’s playground, or anywhere else beyond a two block radius of home. Now he had flushed away all that built-up trustworthiness, because he was overcome with the need to see Addie, the only one in his family who had ever treated him like he had more going on upstairs than an earthworm.

The Illinois that Budda saw now wasn’t at all forbidden-looking, unless a guy was allergic to corn or other grain crops. There wasn’t much to the Illinois color palette, just monochromatic beiges as far as he could see, with not a stripper or crack whore anywhere in sight. When the sanguine sun dropped past the meridian on its way to California, the landscape became speckled with the lights of remote farmsteads. Those must be some lonely people living out there, Budda thought. He hoped Kentucky wasn’t like that. He preferred suburbs like Kirkwood with lots of lights, people, and signs to tell you where to go if you got lost.

Budda switched to a different bus in Indianapolis, which was not as full as the first one. He regarded a girl about his age who sat near the front of the bus. Budda couldn’t make out what she looked like, if she was pretty or plain, but she was the only other young person on the trip, and she seemed much more acclimated to bus riding than Budda did. She got on, sunk into her seat like she was in for the long haul, and plugged in the ear buds to her iPod. He admired and envied her lackadaisical demeanor, as though she had ridden a thousand buses just like this one and nothing could faze her. Conversely, he was sure all the other passengers knew just by looking at him that he was a novice at bus travel. He was the one who couldn’t walk down to the street corner without his father wanting to put a tracking device on him.

Budda mused about what he might say to the girl if given the chance. He had never said more than a word or two to any girl other than Addie, who wasn’t really his sister in a blood or legal way. She had left the Jessico home and moved back to a God-knows-where-hamlet in Kentucky. Addie had told him the name of the place, saying it was near Louisville, which she pronounced “Lou-vull”, like the middle syllable wasn’t worth the effort. Budda remembered that part well, but he couldn’t quite grab hold of the name of Addie’s hometown. He was sure it was stuck in his memory, but buried in there so deeply that he couldn’t bust it loose.

That was another important detail he should have nailed down before he left St. Louis. Taking a minute to scan the Louisville area on Google Maps would have helped him summon up the name of Addie’s town, but he didn’t think of that. That and the fact he didn’t have his sister’s phone number would indicate that his journey wouldn’t go well, but Blood Mama said Budda was just being whimsical. Tomato/tomahto.

The bus pulled into the Louisville station shortly after two in the morning. Budda could tell as the bus crossed the Ohio River that Louisville’s skyline was smaller than the one in St. Louis. He trusted that would make it easier to find Addie. He was for sure going to put everything he had into the effort, because he could never return to St. Louis. His brother would kill him the second he got back inside the front door.

Budda didn’t know what to do now that he was in Louisville. He had no plans for how to start looking for Addie. Second thoughts started to creep into his head just as he was about to step off the bus.

Don’t turn into a weenie on me already, Blood Mama said. You’re not going anywhere but to find and rescue your sister.

I think this was a bad idea, Blood Mama. I don’t even know where to find her, and you’re not telling me what trouble she’s in. What if it’s something I can’t get her out of?

Too late to think like that. Besides, you don’t have enough money for the bus ride back home.

I bet they have a Western Union here. The one in St. Louis did. I could just have Dad send me the money.

You’re not going back. You got to go get your sister, Blood Mama said.

What if she doesn’t want to be gotten?

This isn’t the time for what-if’s. You’ve got to get off your rear right now and start looking before something real bad happens to her.

Panic began to stir in Budda’s gut. If Addie was in such a mess, others were more capable of helping her. Maybe he’d call his dad after all. Blood Mama stopped him before he could pull the phone from his backpack.

This is something only you can do, she said. Nobody else knows the girl like you.

The bus from Indianapolis to Louisville had been less than half full. As soon as the passengers had departed and retrieved their luggage, they quickly dispersed into the city. It was like the terminal had already closed for the night. No one was inside but a woman who swept the lobby floor. Only Budda and the girl from the bus remained in the lobby. The girl asked the janitor if she could suggest any cheap restaurants nearby that stayed open late. That’s the kind of question a smart girl would ask, Budda thought.

“There’s a big McDonald’s up on Broadway that stays open,” the woman said, continuing to corral a pile of paper coffee cups and other trash with her broom. “It’s at Second Street, which isn’t too far. A cab ride wouldn’t cost much. There’s always one or two waiting out front.”

“I’m not real excited about paying for another ride after I just paid for this one,” the girl said.

“Don’t think about getting there on foot. A girl your age ought not to be out walking alone at night,” the custodian said, sounding more like a mother than a Greyhound employee. “You go on and let the taxi take you.”

Unworried, the girl said, “I can do just fine by myself. This place’s a lot smaller than Indianapolis.”

“Maybe,” the woman said. “But that doesn’t make it any nicer. You stay alert to your surroundings.”

The girl strode with confidence toward the exit, an Old Navy overnight bag swinging off her arm. It dawned on Budda that he hadn’t eaten since lunch at school. He decided McDonald’s was where he needed to go, too. It might also be a good idea to keep an eye on the girl, in case she encountered any of those bad elements the Greyhound woman warned about.

The girl walked up Seventh Street and then turned left at Broadway where traffic was heavier. Budda wondered if downtown St. Louis was just as busy at two on a Friday morning. He had never been there that late to know. His dad strictly enforced a ten o’clock curfew on weeknights and ten-thirty on Fridays and Saturdays — no exceptions. The man fretted incessantly, like he still believed in the Boogie Man. He wouldn’t let Budda, Lando, or any of the foster kids that had come through their rambling three-story home, play in the backyard unless he could watch them. He said you never knew when a rampaging maniac would come smashing through their privacy fence and carry them off. And then who would be sorry? This remained the man’s dreadful outlook, even though Budda was approaching six feet and Lando was five-ten and pushing hard against 275 pounds. If anyone needed to worry about being carried off, it was their five-six, 140-pound father.

The parade of foster kids, many of them used to much more lax living environments, hated the house rules even more than Budda and Lando did. Addie bristled most.

“I get no privacy around here,” she said. “It’s gotten to where he’s standing guard outside the bathroom when I take a pee. He knocks on the door and asks if I’m okay in there.”

“It’s for our own good. He’s just trying to keep us all safe,” said Budda, parroting what he had heard Dad say many times. As an adoptee who took his father’s last name, he felt it necessary to defend the man to his temporary siblings.

“Nobody can guarantee anyone’s safety,” Addie said. “If the Boogie Man chooses to come after you, a 43-year-old environmental engineer in tie dye and granola sandals won’t do much to scare him off.”

Until Addie came to live with them, Budda hadn’t felt suffocated by his father’s relentless fretting about imagined dangers. Lando often complained about their father too, but then, he was a chronic complainer. Budda had tuned him out a long time ago. With Addie, Budda began to see things differently. Any time Budda broke a rule, even something harmless like reading a comic book in bed after lights out, he was overcome with guilt for days. But Addie had a different type of conscience. She ignored curfew, ate what she wanted when she wanted, and came and went from the house as she pleased. She didn’t always come home alone either. Budda was certain that she had sex with at least two different boys in her room when their parents were away. And she got away with it.

An orange rear-loading garbage truck rumbled to a halt along the curb just ahead of Budda. A man in a backwards Atlanta baseball cap hopped off the back, thwacked off the lid to a public trash can and dumped its contents in the crusher. As the truck geared up and moved past Budda, he spotted a brown stream of stale beer and other ooze leaking from the back corner of the truck, right where the man rode.

My Lord, you could never get me to live in this place, Blood Mama said. Too much stinky-stink.

Budda had to agree. He wasn’t getting a pleasing first impression of Kentucky. But his ride across Illinois taught him that he should hold off on making any snap judgments.

It’s just normal city smells, he said.

You’re an expert on all things urban all of a sudden? Just keep your eyes on what you’re doing. There’s bound to be all sorts of nasties out on a mild night like this. I can’t wait until we get out of the city and into the country where the girl is.

Blood Mama wasn’t helping Budda conquer his fear of the strange city. Few people occupied the sidewalks, but anyone of them could hide a weapon. He closed his gap behind the girl to about twenty feet. After another block along Broadway, the girl turned abruptly, with something in her raised right hand that Budda couldn’t identify in the shadows.

“I got pepper spray, and I’ll use it on your ugly face if you come an inch closer,” the girl said.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed